‘Everybody just thinks it’s a pay cheque,” says Abe Lee Birham. “I am a ‘bullet adjuster’. I make that part of the bullet that does the killing. Any type of bullets you can think of. We make bullets for the shops. We make bullets for the government. We make specialised bullets. Armour-piercing bullets. They call them cop killers.”

It pays not to think too hard about making bullets on the Winchester Ammunition production line.

“I know personally that I have blood on my hands,” says Birham, who has spent most of his adult life putting together the cartridge cases and lethal lead tips that take 35 lives a day in the US alone. “I’ve made bullets for civilians, for the army. Over the course of 25 years I’ve made millions of bullets. You can’t sit here and say not one of those bullets you have touched has murdered someone. All of us who made them have blood on our hands.”

But Birham says the workers at Winchester in Mississippi, made famous by its rifles in what used to be known as the wild west, tell themselves it’s really no different to making cars that run over people. And anyway, the workers are not the ones pulling the triggers.

The result, crows Winchester, is a fine example of “American craftsmanship”. And a profitable one. American civilians spend more than $1bn a year on ammunition.

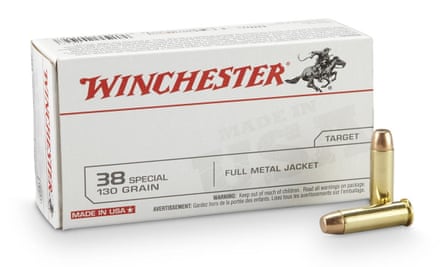

Some bullets go straight to a packing plant to supply the US military’s insatiable demand, even though it’s no longer fighting major wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. But .38 bullets are also popular with civilians and so some are boxed up and distributed to gun shops and supermarkets across the US.

The .38 Special ammunition has been around since 1898. A little more than 1.5in long (39mm), looking a little like a small golden lipstick, it is shorter and less pointed than those used in military rifles and machine guns. The batch headed to the Walmart Supercenter a little more than 1,000 miles away in Easton, Pennsylvania, were packed into boxes of 50. At Walmart they were stacked on shelves with hundreds of shotgun cartridges and bullets of all calibres between the auto care aisle and the bicycles. Two glass cases, with shotguns on sale for as little as $172 (£118), stand sentry at the beginning of the weapons section.

The white Winchester ammunition boxes, with a logo of a cowboy with a six-shooter on his hip and a rifle in his hand whipping his horse into a gallop, were still sitting on the shelf when America’s independence day rolled around.

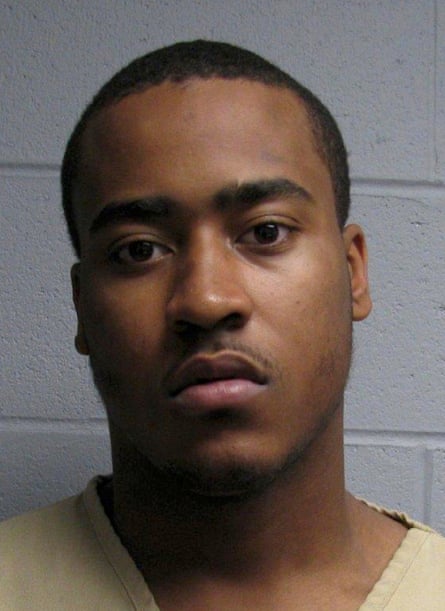

Robert Jourdain had promised to deliver his two-year-old son to the boy’s mother in Easton for the 4 July celebrations. A friend, Kareem Mitchell, offered him a lift from New Jersey in his mother’s Mercedes SUV.

When Mitchell pulled up, Jourdain had another man in tow. He introduced his cousin, Todd West. The three men, all in their early 20s, set off on the 90-minute drive in what a prosecutor later called the “Mercedes SUV of death”.

West was in the back seat with the child when he decided to show off by pulling out a gun. It was a Smith & Wesson Model 10 revolver – an old-fashioned pistol you might expect to see in cowboy films with a revolving chamber that holds six .38 rounds.

More than six million Model 10s have been made in one version or another since it was introduced in 1899. The US sent hundreds of thousands to the British and allied militaries during the second world war. The gun was popular with US police forces for years before semi-automatic pistols came along and is still used by law enforcement in Hong Kong, Myanmar and Peru. Lee Harvey Oswald was carrying one when he was captured after assassinating President John F Kennedy.

Today, the .38 revolver is among the most frequently stolen handguns in the US and in the latter part of the 20th century was reported by big city US police forces as the most often used in murders involving firearms.

Mitchell pulled the white Mercedes into Easton, a former railway hub with a strong German heritage, and dropped off Jourdain’s son. West went to get a haircut. That evening, the three men headed to a nightclub to celebrate independence day. They emerged some time after 2am, at which point West decided that if he had a gun, what he needed was ammunition.

There are not many places to buy bullets at that hour but Walmart – the global chain that owns Asda in the UK, employs more than two million people and pulled in close to half a trillion dollars last year – was open 24 hours and, unlike other supermarkets that took bullets off their shelves after one or other of the US’s regular gun massacres, still stocked ammunition.

The Mercedes parked at Walmart just before 2.45am. West had convictions for robbery and drug possession and so was barred from buying ammunition. The police say he gave his cousin the money and sent him in.

The store was largely deserted as Jourdain passed the cashiers and headed toward sports and leisure. Ammunition covered six shelves, locked behind glass sliding doors. Shotgun cartridges for target shooting and game hunting, bullets for semi-automatics modelled on weapons of war but euphemistically called “modern sporting rifles”, and ammunition for pistols.

A notice taped to the glass limited customers to three boxes of .22 bullets – they were in high demand since Barack Obama became president and rumours swept the more lunatic end of the gun community that he was going to impose a tax on bullets to make them unaffordable. A second wave of panic-buying followed the Sandy Hook massacre of 20 elementary school children and six adults in 2012 amid talk – and that’s all it turned out to be – of tighter gun control legislation.

There was no problem finding .38 bullets though and Jourdain asked an assistant to unlock the cabinet. According to the sales receipt later found in his clothing, he bought a box of 50 Winchester .38 bullets at 2.56am.

The store’s video camera recorded him. The families of the victims claim in a lawsuit against Walmart that Jourdain was visibly drunk after at least four hours in a bar and that he was, in any case, underage to buy handgun ammunition – he was 20, a year short of the legal requirement. Walmart says that .38 bullets could also be used in rifles and so it was permitted to sell them to him at 18. It disputes that he appeared intoxicated and says the cashier entered the young man’s date of birth into the register.

The courts have yet to resolve what actually happened at the till that night but across the US stores are more relaxed about who they sell ammunition to than their almost obsessive prevention of under-21s laying their hands on alcohol. Those who look too young will be required to produce ID to buy a beer but many stores do not ask for proof of age to purchase bullets.

Jourdain left clutching a plastic Walmart bag with the box of ammunition. After he climbed into the front seat of the Mercedes, he handed the bullets to West in the back.

The quickest route from Walmart to the heart of Easton is along Nazareth Road. The fast food joints give way to swish houses and then trees. Turn left at the sign for Bethlehem and almost immediately the north-west corner of the city looms. The drive takes not much more than 10 minutes in the dead of night.

Along the way, West opened the box of .38s and loaded the chamber of the Smith & Wesson. Mitchell steered the Mercedes into Easton’s West Ward, the city’s most populous neighbourhood, and down Lehigh street. It was about 3.15am when West spotted 22-year-old Kory Ketrow walking home from a friend’s house. The young man was just a few feet from his front door when the Mercedes pulled alongside. A detective told a preliminary court hearing that under questioning West told him the young man “looked tired” and that he decided to “help” him. The police officer said West described how he climbed out of the Mercedes, walked up to Ketrow and said: “See ya later.” Then he is alleged to have emptied the pistol into his victim.

Pauline Bader heard the shots from her couch. Ketrow had moved into her house about three years earlier after his mother, who has multiple sclerosis, went into a nursing home. Bader said she instantly recognised that the shots were not 4 July fireworks and bolted out the door to see Ketrow lying in the street. “I said: ‘Kory, is that you?’ And he said: ‘Yeah it’s me, I was shot, I was shot,’” Bader told the local newspaper, the Morning Call, two days after the killing.

The police arrived. Officer Jamie Luise ripped open Ketrow’s shirt and saw several gunshot wounds down the left side of his body and blood pouring from his chest.

Even before Ketrow was loaded into an ambulance, the Mercedes was homing in on its next target. West spilled the spent cartridges from the revolver on to the floor of the vehicle and took six more bullets from the box. The gun was reloaded by the time Mitchell pulled up behind a silver-coloured car at traffic lights about a mile from where Ketrow was shot.

Helene Barone, 45, looked in her rearview mirror, noticed the vehicle behind had its headlights off and then saw a man pointing a gun at her and her passenger. “I said: ‘Oh my God, they’re going to shoot us,’” Barone told a court hearing a few months later. As she accelerated away, West is alleged to have opened fire. Barone heard three shots. She ran two red lights and headed for a police station. The next day Barone noticed her tyre was losing air. When she took it in for repair, the garage found a bullet.

Mitchell headed towards Allentown, a former industrial town that has invested heavily in revitalising its heart. West again tipped the spent cartridges from the revolver and reloaded. About 45 minutes after the killing of Ketrow, the Mercedes turned off the highway on to the main road into Allentown. The next target was only a couple of blocks away.

Francine Ramos was driving a burgundy Honda Accord. The police found the 32-year-old woman slumped over the wheel with several bullet wounds. Her friend, Trevor Gray, bolted from the car but the 22-year-old made it only a few feet. Officers discovered him still breathing, slumped against a parked car. He died at the scene as paramedics tried to save him.

The box of bullets was still more than half full and the police say West jumped back into the Mercedes ready to continue his hunt. But in her death throes, Ramos put an end to the killing and laid the ground for West’s capture. Her Honda collided with the Mercedes, bending one of the SUV’s wheels, denting the front and scraping burgundy paint along the passenger-side door.

Detectives said that West later told them there were still bullets in the box and he wanted to hunt down more victims but Mitchell, worried about the damage to his mother’s car, called it quits. “(West) wanted to keep killing people,” Allentown detective, John Brixius, testified.

The police prepared for a long investigation. They had no description of the murderer. They had no motive. Was there a connection between the victims? Why had the killer struck in Easton and Allentown? It was a mystery to the families and friends of the dead too.

The day after the shootings, Trevor Gray’s father visited the site of his son’s murder where a small roadside memorial with a picture of the young man with a goatee and gold chain was taped to a lamppost. Joseph Gray was as baffled as everyone else as to why his son was killed. Trevor worked with mentally disabled children and was in his church’s choir. “He had a heart of gold. He was loved by most everyone,” Gray told a local television station.

Ramos was a mother of three boys and worked as a cashier at Dick’s Sporting Goods. She met Gray while he was working as a bartender.

Ketrow, who friends remember as a member of Skate Church – a mix of skateboarding and Bible study – was walking back from Mark Yedlosky’s house when he was shot. Yedlosky’s father woke him hours after the murder to say the police were at the door. “I couldn’t believe it was happening and why someone would do this. They got the wrong guy,” Yedlosky told lehighvalleylive.com.

Before the shootings, Jourdain had arranged to stay with a friend, Danielle Smith, in Allentown. He turned up at the third floor flat in the middle of the night with West and Mitchell. They left the Mercedes in the carpark next to the apartment block with the box of bullets and the gun in the Walmart bag on the back seat.

Detectives had one major clue. A witness described a white SUV making a getaway from the scene of the Ramos and Gray murders. Given the state of Ramos’s car, the police suspected it was damaged.

A few hours after the killings, a police officer spotted the vehicle in the carpark. A search of the Mercedes turned up the .38 calibre Smith & Wesson revolver along with the partially empty box of bullets; 18 spent cartridge casings were scattered inside the vehicle.

West, Jourdain and Mitchell were still upstairs in Smith’s flat.

The killings were leading the news in part because of their shocking and random nature. There are not many murders in the region known as Lehigh Valley – a total of 14 last year, including a baby tossed off a bridge – so they were getting plenty of police attention. The district attorney was in front of the cameras promising to catch the killer.

In such circumstances it might be thought West and Jourdain would go to ground or get out of town. Instead they woke up the following morning, decided they needed money and, according to the indictments, set about robbing people at knifepoint in the city centre.

The pair allegedly mugged three men, getting away with a total of $29, a cellphone and a green lighter. West and Jourdain were still on the street when a police officer spotted them and thought they looked like a pair of robbers one of the victims had just reported. When they ran, he gave chase.

When West and Jourdain were finally arrested and hauled into a police station they were not even suspected of murder. But things started to fall into place fast. The police had traced Mitchell’s mother, who owned the Mercedes, and then found her son. When officers ran West’s name through the computer they discovered he was wanted for a series of killings a few weeks earlier in his hometown of Elizabeth, New Jersey, about a 90 minute drive east.

There West is accused of shooting his cousin, Michael Thompkins, in the hallway of his apartment building on 18 May. He is also charged with four apparently random shootings on a single day in June. Three of the victims died and a fourth was gravely wounded. All were shot with a .38 revolver.

Shortly before midday on 6 July, Inspector Daniel Reagan and Detective John Brixius confronted West and, according to the criminal complaint, he admitted to the murders in Allenton and Easton. The evidence was all there. The car. The gun. The box of ammunition. Detectives found the Walmart receipt for the .38s in clothing Jourdain left at Smith’s flat. The police said Mitchell and Jourdain admitted their roles but pointed the finger at West as the instigator and trigger man.

The motive remained a mystery. When detectives asked West why he killed Ketrow, he replied: “He was just a guy in Easton.” Brixius told a court hearing that under interrogation West said he heard voices telling him not to be so fussy in selecting his victims. “The voice was telling him: ‘Eat, eat, stop being picky, eat,’” the detective said. The parents and friends of the victims have been discouraged by the authorities and lawyers from speaking publicly until after the trial but they too want to know why.

The 18 spent .38 cartridges and remaining box of Winchester bullets are locked up in an evidence room awaiting the first of a series of murder trials. Prosecutors are seeking the death penalty for West. Jourdain and Mitchell face spending the rest of their lives in prison.

The Winchester production line continues to run day and night, all week – part of an industry making enough bullets in the US each year to shoot every American 30 times over. Winchester Ammunition alone had total sales of more than $700m last year. In February, the company won a $99m contract to supply .38 and other ammunition to the US army over the next six years.

Its profits have been further boosted by putting employees like Birham out of work. The 52-year-old lost his job last year as the company moved out of its traditional base in East Alton, Illinois, to hire non-unionised and therefore cheaper labour at two sprawling warehouse factories on an industrial park 10 minutes’ drive north of downtown Oxford, Mississippi.

The killings in Pennsylvania went unnoticed by Winchester’s staff in Mississippi. The few prepared to speak do so anonymously, with one eye on the sacked workers in Illinois. They shrug off questions about how the bullets they make are used: “It’s a job”, “You want to blame me?” and “It’s sad but, honestly, I never think about it”.

Their principal complaint is that the demand for bullets is so high, overtime is all but obligatory. One worker, however, says that on the plus side, the company has a high regard for safety.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion